Books and Bibles with silver or even gold locks were made in numbers in past centuries. Intricately worked, full silver bindings like this example however, are extremely rare and were only available to the elite. Not many extremely refined decorated silver bindings are known to have been made in and around Amsterdam.

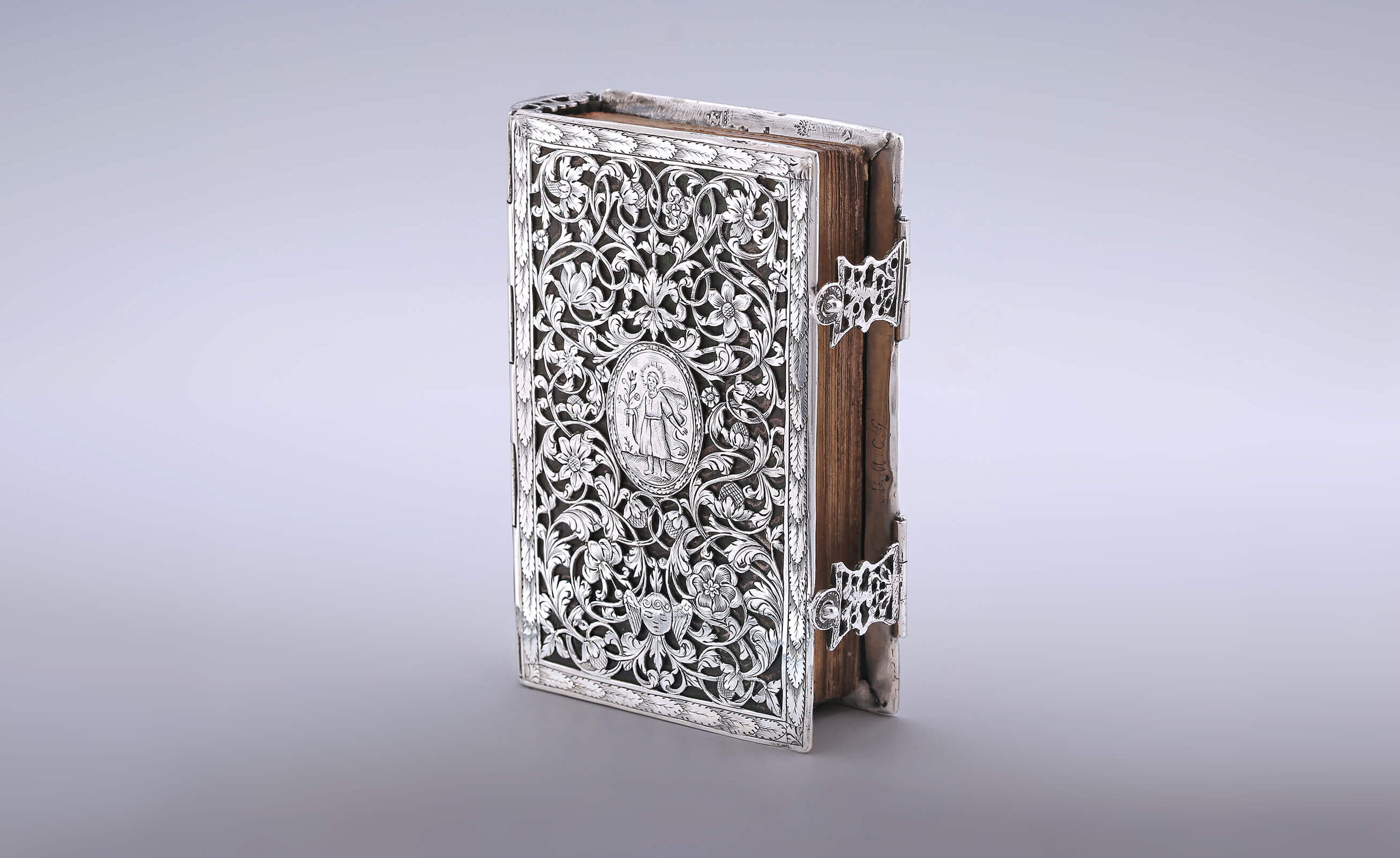

Silver Book Binding

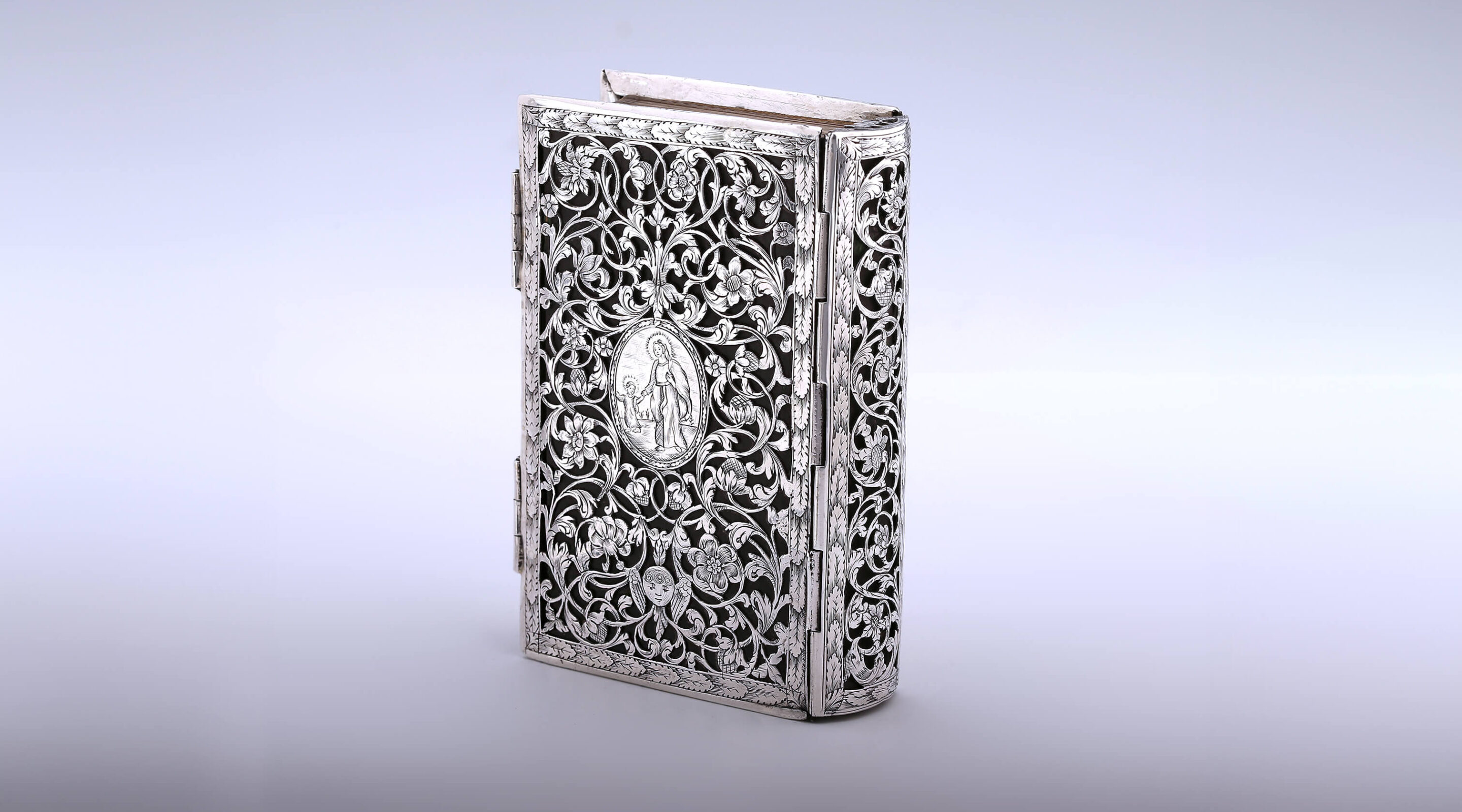

The front and back plates of this binding are made entirely of silver, with very finely engraved and then sawn out floral motifs. The decoration is built up from continuous tendrils of vine leaves that curl over both sides and the spine. It includes different types of flowers and pomegranates, surrounded by an engraved border with a stylized acanthus leaf motif. There is a medallion of St Joseph in the centre of the front cover and one featuring the Virgin and Child on the back. Under the medallion on both sides a winged cherub’s head has been incorporated into the vines. The two silver clasps that keep the book closed are openwork. The cut edges of the book block are gilded; an old book decoration technique used on costly editions. The caps, the turned-in edge of the spine cover at the top and tail of the binding, are beautifully finished with a pattern of pomegranates with a tulip between them.

Bindings

In emulation of the Copts, from as early as the seventh century, bindings were fitted with complete or partial metal closures in Europe too. The covers were held together when the book was closed to protect the contents from damp and pests, such as insects or mice. Aside from this practical function, books also acquired extra prestige if metal – particularly precious metal – was used on the clasps. It was predominantly folio volumes that were given metal clasps and hinges, mostly of brass. Later small bindings were adorned with metalwork. This phenomenon increased throughout the seventeenth century in the Netherlands.

Designs

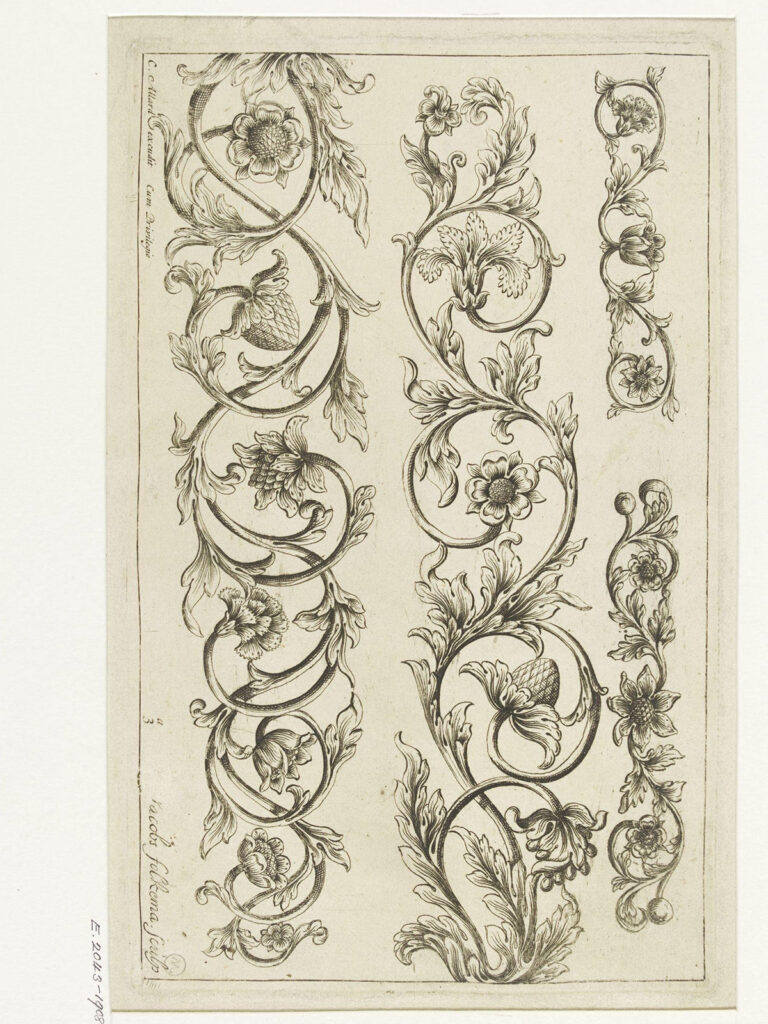

The decoration of this silver binding was clearly inspired by the designs of Johannes Jacobszoon Folkema, which around this time also served as inspiration for decorations in cut-card technique. It was a technique that was used for a relatively short period, between c. 1690 and 1715. The floral and foliage motifs on this binding bear a strong resemblance to some series of prints by him that appeared in Amsterdam around 1695 under the name Doorgebroken Zilver-Smidswerk.

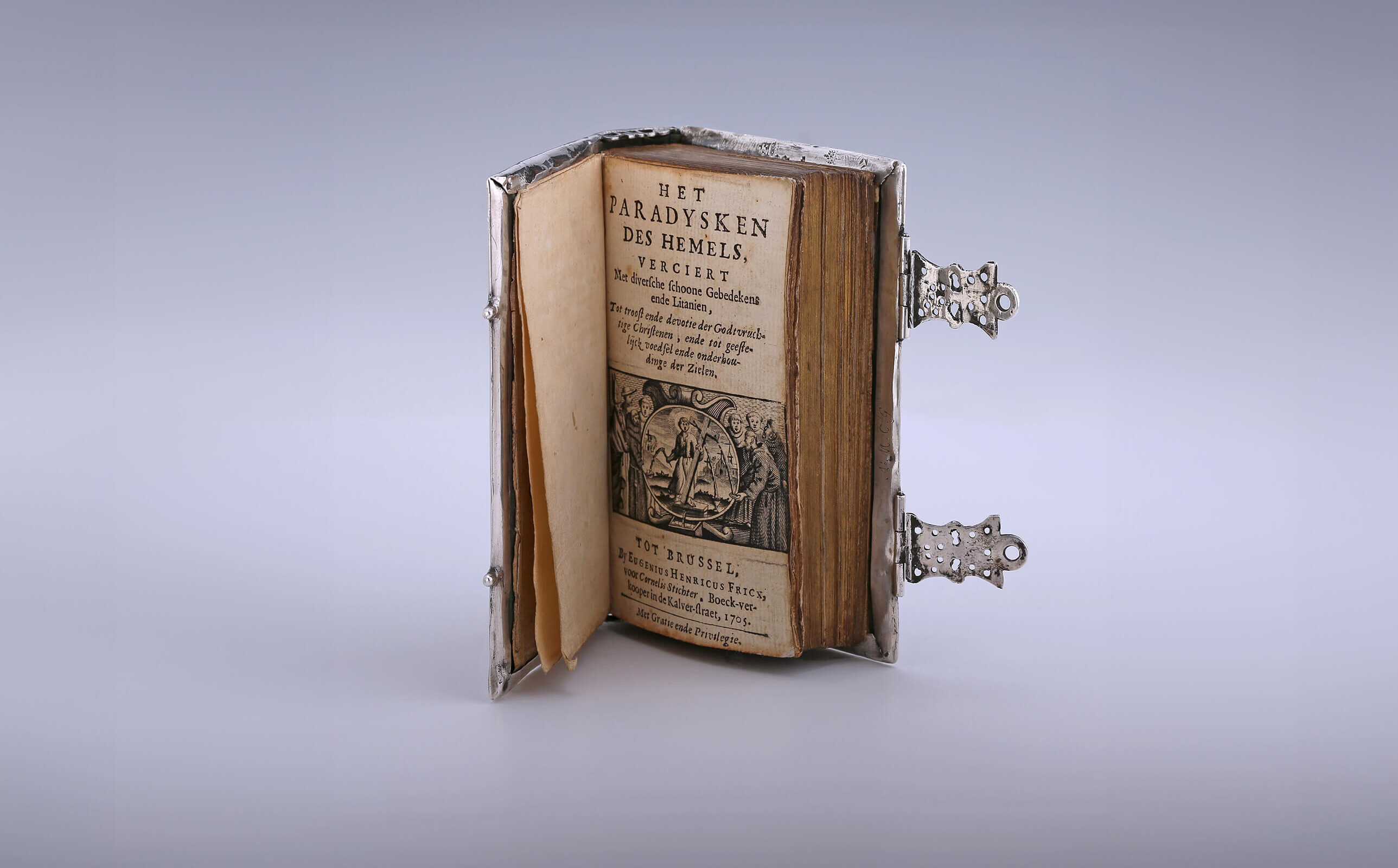

Het Paradysken des Hemels

This silver binding contains a service book for Roman Catholics of Amsterdam, who had to hold their masses in the then Protestant Amsterdam in secret conventicles. As well as all the Christian feast days from 1706 to 1730, all the prayers required throughout the year were included in it. To start with Oeffeninge des morgens (matins), continuing with Om den Dagh Godtvruchtelijck (Daily Worship) until the Vesper Psalms, with a handy Table (list of contents) at the back. Although many prints and reprints of this title appeared, there are now only six other copies of this little book in the Netherlands, all of which are now in libraries. None of them has a silver binding. A new version ‘Het Vermeerdert Paradysken’ was published in 1750 and remained one of the most popular among the more voluminous prayer books in Roman Catholic Netherlands until well into the nineteenth century. It was distributed from Turnhout and Mechelen.

Ecclesiastical Approbation

Below the engraved title vignette, the title page gives further information about this little book. At the bottom of the page is the name of the printer, Eugenius Henricus Fricx, who was in business in Brussels, together with the name of the bookseller for whom he had printed the book: Cornelis Stichter, bookseller in Amsterdam’s Kalverstraat, 1705. At the back of the book is the approbation – approval – of 29 July 1675 of P. de Roeck, book censor of Brussels. Such ecclesiastical approbation was mandatory at that time and had to be carried out in the parish of the printer or bookseller.This purpose of this precensorship was to prevent heretical views from circulating and lecture notes with ‘degenerate’ text from being spread in the universities On this last page there is also an extract of the Privilege, dated 29 May, 1700, stating that Eugenius Fricx had the sole right to print this book for period of nine years.

Eugenius Henricus Fricx

The Brussels printer of this book, Eugenius Henricus Fricx (1644-1730), was the son of a haberdasher. His marriage to Barbe Mommaert brought him into a family of book printers. Her brother, Jan II Mommaert, worked as a printer. Fricx succeed his brother-in-law in 1670 and became the founder of a major dynasty of printers in Brussels. He even became ‘Imprimeur de Sa Majesté’ in 1689 and of his Imperial and Catholic Majesty (1715). He printed dit Het Paradysken des Hemels for Cornelis Stichter, a celebrated bookseller in Kalverstraat in Amsterdam.

Provenance

This binding was in the possession of the English Bateman family in the nineteenth century. The Ex Libris on the inside of the flyleaf bears the coat of arms of this Protestant family. The Bateman family first appears in records in England in the mid-fifteenth century. This binding probably belonged to Richard Thomas Bateman (1794-1853). In 1820 he married Maria Magdalena Willoughby, who was Roman Catholic, and he appears to have converted to that denomination. The couple had fourteen children and lived at various addresses around Bath. On the last page at the back of the book there is a collection sticker with the initials RM for Robert May (1875-1961), an Amsterdam Banker and avid art collector. May was a member of the Amsterdam bank Lippmann, Rosenthal & Co in Nieuwe Spiegelstraat and had a considerable collection of paintings, porcelain and silver. The initials A.M.C.G. of an unidentified owner are engraved on the silver edge at the back.

Date

The few currently known Dutch silver bindings do not have silver hallmarks and, on stylistic grounds, often in conjunction with the date of the book they contain, are placed in the first quarter or in any event the first half of the seventeenth century.

This silver binding however, is the only one we know of that is fully marked. Alongside the Amsterdam city assay mark it is also struck with the Dutch Lion mark, which was mandatory in the provinces of North and South Holland after 1663. It also bears the date letter R.

This book is illustrated in volume II of the books on Dutch silver by J.W. Frederiks, where it is dated to 1671. Given the model of the city assay mark, we can now precisely date this binding to 1703 which corresponds with the design of the decoration of the silver after Folkema’s prints and the date of the book it contains. Unfortunately, the maker’s mark is illegible.