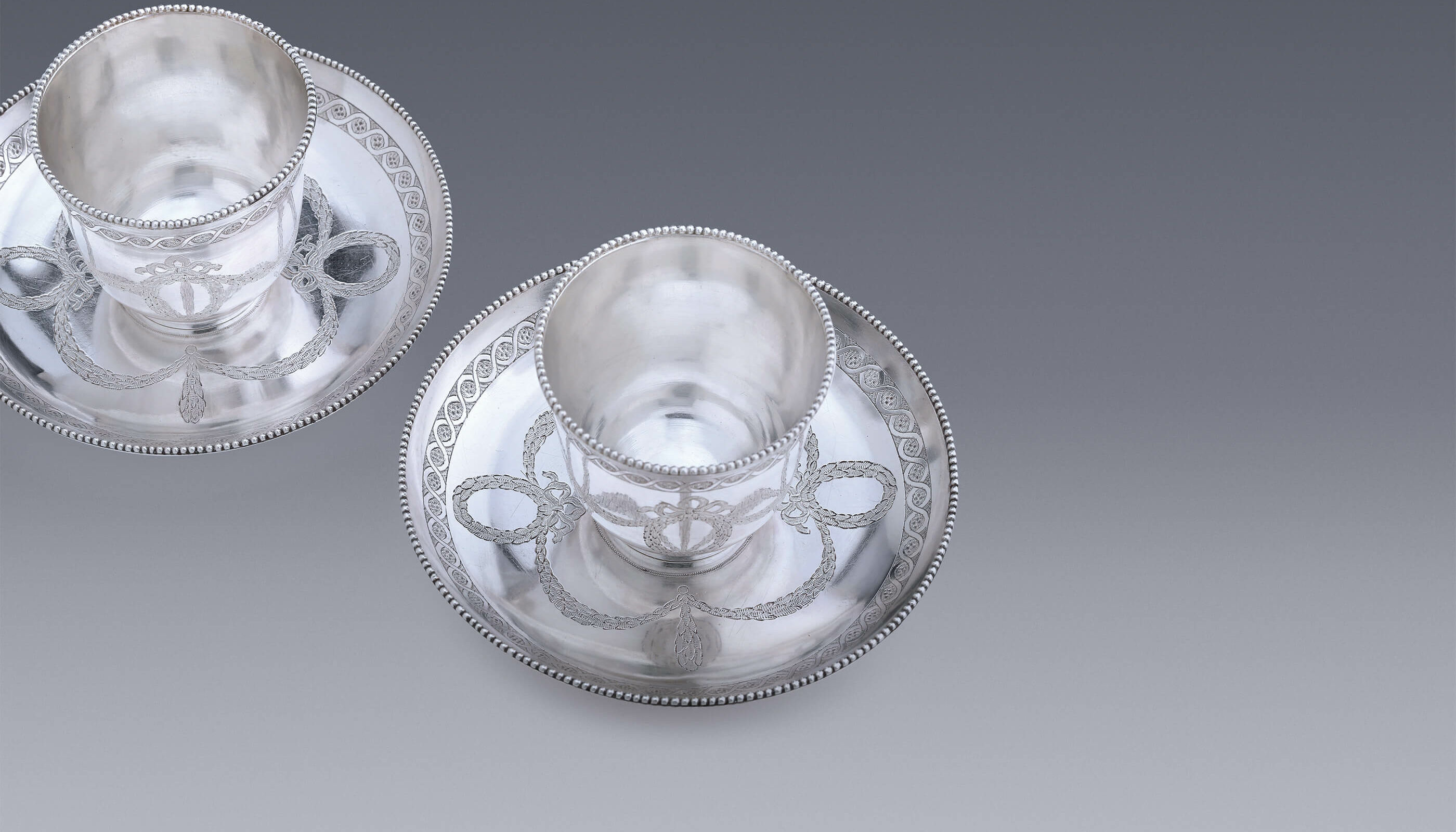

This very rare pair of silver cups and saucers was made by the Amsterdam silversmith Barend van Mekelenburg in 1780. The round saucers and the cups both stand on a foot ring and are decorated with a beaded edge, an engraved decorative band with two meandering lines and engraved garlands of laurel leaves and bows. On the cups the garlands form a medallion tied with a ribbon on either side.

A Pair of Cups and Saucers

Rare

Dutch silver cups and saucers like this are extremely rare. At present we know of only five examples—one in the collection of the Amsterdam Museum, one in a private collection, and this pair. All five were made by Van Mekelenburg and they are all hallmarked with the date letter V for 1780, which suggests that they might have been part of a set or service. They may be regarded as a translation into silver of pieces made in porcelain.

Coffee

At the end of the sixteenth century, merchant vessels trading with the East brought coffee, tea and cocoa to the Netherlands for the first time. Although Dutch East India Company merchants traded coffee between the Arab countries, it was not until the second half of the seventeenth century that large shipments of coffee reached the Netherlands. Before that, coffee beans were brought back in small quantities by seafarers. They were sold by apothecaries for their supposed medicinal effects. In the Netherlands the exotic, still exclusive, drink was enjoyed by only a few people in the wealthy patrician class. ‘Turkomania’, a new fashion that began in France, swiftly boosted the drink’s popularity. People wanted to dress and behave like Orientals, and coffee-drinking was part of this. Coffee houses sprang up everywhere.

Mokha

The original porcelain version of this tall cup was sometimes described as a Mokha cup. At that time Mokha was known as a top quality—and hence very expensive—coffee bean, named after the Yemeni city of Mokha. To this day, Mokha coffee beans are known for their strong flavour with a hint of chocolate.

Mokha (Arabic: Al-Mokha or Al-Mukha) was founded in the fourteenth century. From the fifteenth to the seventeenth century it was the most important coffee-trading centre in the world. The Dutch did not start trading with Mokha until the seventeenth century, when the Dutch East India Company set up a trading post there. The first coffee auction was held in Amsterdam in 1661: 21,481 pounds of mokha coffee went under the hammer.

Mokha had a monopoly on the coffee trade until Dutch East India Company employees smuggled a few coffee plants out of Yemen at the end of the seventeenth century. The Dutch then established coffee plantations on Java.

Amsterdam

In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century Amsterdam was the world centre of the coffee trade. Over time, the coffee grown on Java overtook production in the Middle East. Plants were brought to Amsterdam and grown as curiosities in hot-houses. In 1715 the burgomaster of Amsterdam gave the French King Louis XIV a young coffee plant for the Royal Botanical Gardens in Paris. This plant was the progenitor of billions of coffee plants all over the world. As the greatest coffee drinkers in Europe, the French wanted to produce their own coffee rather than buy beans from other nations. A French naval officer sailed to the Caribbean with cuttings from the Dutch parent plant. As the result of his endeavours, around 1775 there were eighteen million coffee bushes growing on the island of Martinique, a French colony—all from that single Dutch cutting. Coffee-growing and the coffee trade soon spread all over the world.

Barend van Mekelenburg

Barend van Mekelenburg, the oldest son of the goldsmith Staats van Mekelenburg and Mayke Vink, was born in Leers around 1751. In 1779 he was enrolled as a citizen and silversmith in the city of Amsterdam, where he lived on Looiersgracht. He died in 1823. We know of trays, tobacco jars and coffee pots made by him. He was a productive maker of tableware. His brother, Pieter Staats, submitted his masterpiece ten years later, in 1789. He made small items of tableware.

Both cups and saucers are marked with the Amsterdam assay office mark, The Dutch lion, the date letter V for 1780 and the maker's mark BVM for Barend van Mekelenburg.

Diameter of the saucers 12 cm; height of the cups 5.8 cm; The weight 170 and 171 grams.

Literature

Catalogue Goud en zilver met Amsterdamse keuren, Amsterdams Historisch Museum. Page 192 no. 96.