This large tea chest is built up entirely of filigree panels. When the lid of the Batavian chest is lifted, we find a solid and intricately engraved silver inner plate into which two oval tea caddies fit, made in The Hague by Reinier van Stapele in 1794. The two wholly silver caddies have the original lead lining to best preserve the tea.

The sides of the chest are decorated with scrolling motifs, volutes and rosettes mounted in a framework. The domed lid is vaulted. The two oval tea caddies in the chest have lids that taper up towards the middle and are engraved with foliar motifs around a stylized finial. They have beaded borders. The chest stands on four flattened ball feet, which are also made entirely of filigree. Two C-shaped handles hang on the sides of the chest and a heart-shaped filigree clasp is mounted on the lid.

Technique

The technique used to make this silver wire tea chest is known as filigree. Fine silver is pulled out to make gossamer-thin wires. A wire several metres long can be pulled from just one gram of metal. The wires are twisted around one another and then flattened. This forms the basis for the filigree work. The wires are bent into different motifs inside a framework of slightly thicker silver thread. When the panel that has now been made is ready, solder milled to fine grains is sprinkled over it. It is then heated in a charcoal fire which has to be stoked up so that the solder grains melt and fix the wires. The word filigree is derived from the Latin words ‘filum’, ({thread) and ‘granum’ (grain), which are joined to make the Italian word filigrana and the French filigrane. In Dutch it was called filigraan or filigrein, until the nineteenth century, when it was Gallicized to filigrain, a word that does not actually exist in French.

Filigree and the Dutch

In the Ancient world, in the second millennium BCE, a refined filigree technique was used in Egypt, Crete and Greece and by the Etruscans. The technique spread through trade routes in the first millennium CE. In Armenia, Arabia and later in medieval Russia, new centres of craftsmanship and precious metalwork were built, and the filigree technique developed further. The technique was also used in the Far East.

The Dutch became acquainted with filigree through the voyages of the Dutch West India Company (WIC) and Dutch East India Company (VOC). Objects made using this technique are listed as ‘Chinese work’ or ‘Indian silver’ in seventeenth-century Dutch inventories. It was not until the last quarter of the seventeenth century that we come across the word ‘fildegreyn’. Chinese silversmiths from Parian (present-day Manila), Canton and Macao, and from Goa in India, were highly skilled in filigree work. It was most advantageous for them to settle near the major trading posts. From 1661 onwards, Batavia was the VOC’s most important and largest trading station. It is likely that the majority of Oriental filigree came to the Netherlands through this city. Filigree chests could be made to order through the crews of the Dutch East India Company vessels in the Far East and brought back with them to Europe. In the Netherlands these exotic filigree chests were often repurposed as tea chests by adding an interior with one, two or three silver tea caddies made by silversmiths on the spot.

Moisture and Light

In 1667, for the first time, a large consignment of tea, for which there was no interest in Batavia, was brought to Amsterdam by the VOC. Confounding the VOC’s expectations, the tea was seized upon by the public and immediately proved to be a highly profitable product. Imports into the Dutch market rapidly increased in volume. Tea was a luxury product that could be sold for high prices. The tea had to be kept carefully because moisture had a very adverse effect on its quality. People kept their tea in lead canisters, which often had an extra inner lid. To be on the safe side, they added a piece of charcoal to absorb moisture.

For everyday use, people kept small amounts of the expensive tea in the ‘salon’, the most luxurious room in the house, where the lady of the house received her guests. At the time this tea chest was made, she would have all the attributes for the tea ritual: tea-tables, silver trays, teapots, cream jugs, sugar bowls, bonbonnières and Chinese porcelain saucers. The more objects one owned and the finer and more expensive they were, the better.

Three Generations of Silversmiths

Reynier van Stapele was the scion of a Hague family of silversmiths. His grandfather François was recorded in the oath book in 1723. In 1757 Francois’s son Martinus followed; he died around 1805. He was married to Anna Maria de Haan, the daughter of the silversmith Reynier de Haan. They had at least one son, Reynier van Stapele, who made the fine interior for this filigree chest. He was recorded in the Hague oath book in 1788. At the beginning of his career, Reynier worked with his father under the name Martinus van Stapele and son. He had several important commissions, including the gold Communion set for St James the Greater’s church in The Hague. He died in 1795 when he was just thirty.

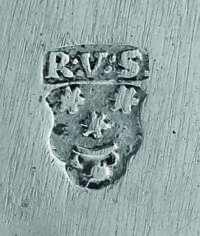

Marks

Both tea caddies are fully marked with the Dutch Lion, the city assay mark for The Hague, the date letter X for 1794 and the maker’s mark RVS above a pot for Reinier van Stapele.

Provenance

Private collection The Netherlands

Collection A. Aardewerk 1993

Private collection Belgium