This very early marriage cutlery set has finely engraved silver handles with grotesques and cartouches containing scenes from the Bible. The names of the couple and 1590, the year they married, are engraved on the sides.

Silver spoons, forks and knives of Netherlandish origin from before 1600 are extremely rare. Most utensils were then used for serving and carving. Knives with representational handles or important ornamentation were very much more costly than less ornate ones, even more so when they were made of silver. Their use was confined to the affluent classes. In the course of the sixteenth century the silver marriage cutlery emerged in the Low Countries, which the prosperous groom gave to his bride with inscriptions of both their names. The set consisted of an iron knife and a fork with a flat silver handle. The silver handles, elegantly scalloped at the end, had a moulded finial.

Sixteenth-century sets like this one are vanishingly rare

They were decorated with marital related biblical scenes or figures, surrounded by late grotesque ornaments in relief against a dark background. There are several surviving seventeenth-century examples of such knife and fork handles in silver and niello, most of which are in museum collections. Sixteenth-century sets like this one are vanishingly rare. Those that are known are famous for their refinement and quality of the engravings on the handles.

The Engravings on the Knife

The engravings on the handle of the knife are divided into different sections. The name of the bridegroom, Jehan van Dallem, and the date 1590, are engraved on one side. The inscription on the other side reads rien sans peyne 1590 . The instruction ‘nothing without effort’ alludes to the two biblical stories engraved on each side. A scene from Genesis III, the Fall of Man, depicting Adam and Eve who have eaten from the forbidden tree. They have realized that they are naked and, ashamed, are covering themselves with fig leaves. On the other side there is a scene from chapter VIII in the apocryphal Book of Tobit. We see Tobit’s son, Tobias, and Sarah, praying to God. In the background is a bed with a canopy. In the topmost part of the handle there are two winged figures between clusters of fruit. Above them, in a round frame, are two clasped hands holding a burning heart. On the other side there is a pelican feeding her young.

The Engravings on the Fork

The handle of this fork is engraved on one narrow side with the bride’s name, Magrite van Ydeghem. On the other side is the inscription rien sans avis 1590 -‘nothing without consideration’. The decorations on the front and back of the handle are divided into sections in the same way as the knife. The bottom compartment contains floral tendrils on a chequered background. Two satyrs hold aloft a banner with scroll work that refers to the subject of the scene in the panel above.

Two clasped hands are holding a burning heart

On one side there is a scene from the story of Susanna. Two elderly men stand around Susanna and touch her while she bathes naked in a fountain. She cringes away from them. On the other side the banner is held up by two wasps and Genesis II is pictured. It is a scene in the Garden of Eden, the earthly paradise, and we see the arm of God, creating Eve from Adam’s rib. Both scenes are surrounded by pillars topped with an arch. This handle has the same decoration at the top with two clasped hands holding a burning heart on one side and a pelican feeding her young on the other.

Southern Netherlands

The family name of the bride, Magrite van Ydeghem, can be traced back to an old knightly house, Ydeghem or Yedeghem, of West Flanders. In the period before this cutlery was made, however, the dark days of the Spanish occupation and the Reformation fuelled large migration movements between the Southern and the Northern Netherlands. This means that it can by no means be taken for granted that Magrite van Ydeghem was still living in West Flanders when she got married. The grooms name, Van Dallem is rather common. Around 1590, we come across this name in both Brussles and The Hague.

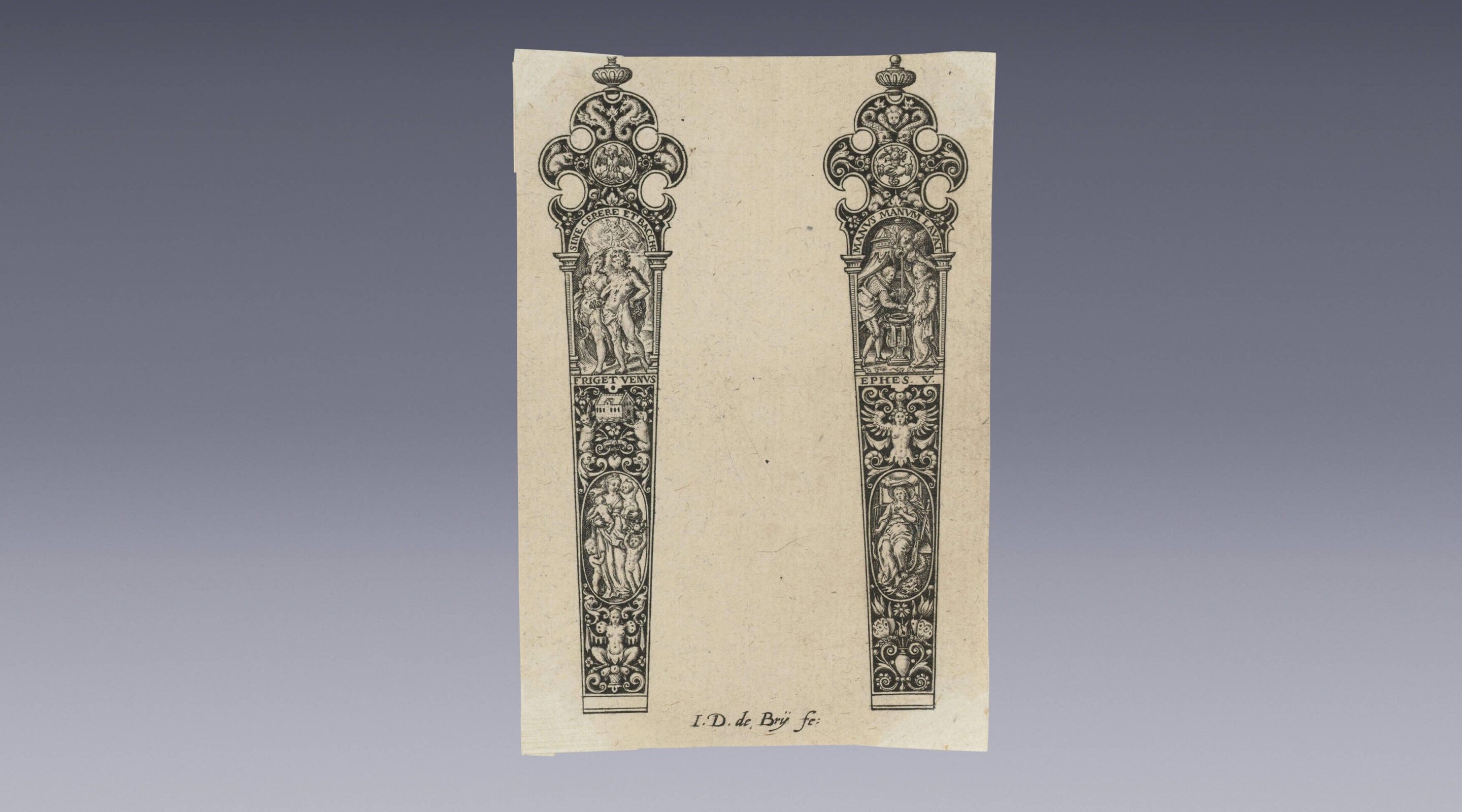

Although both the shape and the decoration of the cutlery followed the designs in prints by Johann Theodor de Bry, who was originally from Liège, we know that these prints also found their way to other silversmithing centres and were used there. Examples of knives and forks like these are listed in inventories in both the Northern Netherlands and the Southern, Flemish, Netherlands. Because the known sets of marriage cutlery are not hallmarked, it is not possible to establish exactly in which city this set was made.

Johann Theodoor de Bry

The ornaments and images were taken from copper engravings designed specifically for the purpose. Most of the designs are anonymous, but there is a relevant print by the engraver Johann Theodoor de Bry in Museum Boijmans van Beuningen’s collection (see above).

Johann Theodor de Bry was born in Strasbourg in 1561, the oldest son of the silversmith and printmaker Theodor de Bry and Katharina Esslinger. He learnt his trade from his father, who was best known for his prints of early European expeditions to Latin and South America. His father had converted to Protestantism, and the Spanish Inquisition meant that the family was forced to flee Liège in 1570. They spent time in Strasbourg, Antwerp and London, before finally settling in Frankfurt in 1588. Both Johann Theodor and his brother Johann Israel worked for their father’s publishing house. After his father’s death in 1598, Johann Theodor took over the family business. He died in 1623.

Bible Stories as Moral Examples

The rise of non-devotional scenes from the Bible in the interior is associated with biblical humanism, a spiritual trend that sought to reconcile the Christian tradition with Classical culture that began its rise at the same time as the Reformation. In the first instance this biblical humanism was found mostly in scholarly circles and had its repercussions on the interiors of the urban social elite. Although biblical humanism was found chiefly in Protestant circles, it must also have influenced Catholic environments. The subjects used as illustrations in many household objects in the Netherlands were taken from the Old Testament. The Bible stories served as moral examples, where the good and virtuous were contrasted with their opposites.

The Story of Susanna

Susanna is a woman in the apocryphal Book of Daniel. She was a beautiful, God-fearing, virtuous woman, married to the wealthy Joachim. One day she was bathing in her enclosed garden, safe in the belief that nobody could see her, but she was mistaken. Two elders (magistrates) spied her there and made indecent proposals. They threatened Susanna, declaring that if she did not give in they would accuse her of adultery, an offence for which the punishment in the Torah was death.

The elders were themselves condemned to death

Susanna still refused to accept their advances and the next day she was arrested and condemned to death by the magistrates. But as Susanna was being led away, the young Daniel stood up and succeeded in catching the elders in their conflicting stories about what had happened. Susanna was acquitted and the elders were themselves condemned to death. Susanna’s story was told as an example for women and was widely applied and depicted on pieces of furniture in the house that were used by women. It was a positive example for women from the Old Testament. It was also a popular subject for artists because it gave them a legitimate reason to picture a naked female body.

Genesis II and Marriage

On the sixth day after God had created the world, he made a man from the dust of the ground. He created the Garden of Eden with the tree of life and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil and put animals into it. He created four rivers to water the garden and then put the man into the garden to take care of it. God told him that he was free to eat from any tree in the garden except the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. But the man was alone. While he slept, God took a rib from the man, Adam, and made from it a woman, Eve, as a companion, and brought her to Adam. And Adam said: ‘this is now bone of my bones, and flesh of my flesh: she shall be called Woman because she was taken out of Man. Therefore shall a man leave his father and mother, and shall cleave unto his wife; and they shall be one flesh. And they were both naked, the man and his wife, and were not ashamed.’ This statement that shows marriage as God’s creation was, of course, eminently suitable for a set of marriage cutlery.

Adam and Eve

On this side of the knife-handle the story of Adam and Eve and the Fall sheds light on the other side of life: the side where the woman is not such a good example. Eve was the embodiment of evil; she was seen as the gate to hell. Finally, Eve’s action burdened mankind with original sin. She can thus be seen as the archetype of the infernal woman, while the immaculate holy virgin Mary is the ‘divine’ woman. In real life the image of Eve was seen as more applicable to women than Mary and was a moral warning.

It is not good for the man to be alone

Tobias VIII

Tobias, Tobit’s son, wants to marry Sarah. But Sarah’s seven previous husbands have died on their wedding night. When they retire to their bedchamber after the wedding feast, Tobit suggests they should pray to together to God and beg the Lord to take pity on them. ‘Blessed are you, God of our ancestors, and blessed is your name for all generations. May the heavens and all your creation bless you forever. You made Adam, and you provided him with his wife Eve to be his help and support, and from these two the human race has sprung. You said, “It is not good for the man to be alone; let us provide him with a helper like himself.” 7 And now I am taking this kinswoman as my wife not out of lust but with sincere love. Grant that she and I may obtain mercy and that we may reach a happy old age together.’ Then together they said ‘Amen, amen.’ Then they slept together. Sarah’s parents had a grave dug as a precaution, but the following morning it proved unnecessary: God was merciful and had blessed their marriage. The grave was filled in before sunset and Tobias and Sarah lived a long and happy life.

Clara Peeters

This type of knife can sometimes be found on 16th-century still lifes; a few paintings by Clara Peeters feature one as can be seen on this detail of the painting ‘Still life with Cheeses, Almonds and Pretzels’ she made in 158, now in the collection of The Mauritshuis, where she placed her signature on a knife very similar to the one here.